|

Shilling

|

LOA 22' LWL 16'6" Beam 8'0" Draft 4'0" Displacement 7,290 lbs. Headroom 6'3"

Only 7 feet longer than Farthing, Shilling is a much bigger boat and the extra size produces some significant gains, taking the overall design concept well beyond minimalist goals. The interior is sufficiently large to provide up to four berths, and gives full standing headroom along with more floor area and space for a larger galley. The layout shown is but one of many possibilities. Another big gain is the ability to easily carry a 7' pram on deck, as shown. There is seating on deck on, or between, the deck boxes. Beam was held to the maximum for legal trailering without a permit in all of the states in the US. However, the limit is now 8'6" in most states in the United States.

A boat of this size and weight is not trailerable in the usual sail-it-off-the-trailer sense, but in areas with sufficient tide she can be floated on and off a properly designed trailer or put on or taken off with a Travelift™ or crane. A 3/4 ton pickup will probably suffice for towing. She'd be a good camper on the road, and can easily make her way to far-off cruising grounds in that manner. But with her excellent offshore characteristics, most people will want to sail her there.

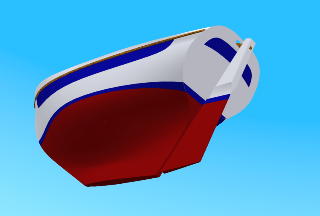

Recently one of our advanced design students Mark Evans was visiting from the United Kingdom and for fun while he was here sat down at a spare CAD workstation and started helping us to refine Shilling so that the design can be efficiently produced as a kit. We believe that we'll be able to eventually produce a super complete, super high quality kit with all parts pre-cut, all the hardware cast and machined, and complete with building jig for right around what the average amateur builder would pay for the raw materials. These kits would be complete right down to the paint and would save an immense amount of the labor that would normally go into building a boat from scratch. Mark produced several renderings that I believe are well worth looking at. Some of these are shown below:

|

|

|

| Mark's basic Shilling forward quarter view | Aft quarter view with stern badge | Very basic fish eye view |

Shilling is the 22’ version of our Coin Collection. She’s most suitable for those seeking contentment living aboard a small simple boat with a good companion; seeing the world at their own pace. For those with limited time she can be trailered behind a good sized pickup to the ocean you want to cross, without any special permits.

Reports of unusual speed repeatedly surface, when talking about little but heavy vessels. We have certainly personally observed some remarkable performances. This results from three factors common to designs such as the Coin Collection vessels, the Vertue class, and other heavy, rugged, small voyaging yachts.Their great weight in relation to their length, needed for carrying capacity, results in much lower wetted surface in relation to their sail area than today's average. This gives them speed in light airs. They are stiff in heavy weather, which again helps their sail carrying capacity. The only time they don't have a clear advantage over more average boats is when winds are moderate. The third factor is an unusual one, involving some controversy. Upon first seeing designs like my Shilling and those mentioned above with immersed transoms with outboard rudders, the observer might think, "that'll slow her down. It has to add drag, doesn't it?" Well, generally it's safe to say that anything that interrupts the smooth flow of water restricts speed and anything that promotes non-turbulent flow increases speed. If we now view the problem in this manner, things look a little different. The question now becomes whether on a particular vessel that immersed transom will help or hinder the water flow. On most boats the water flow becomes turbulent, in any case, by the time the aft sections are reached. Thus the harm caused by the underwater portion of the transom will be minimal. Further on some vessels immersing part of the transom allows straightening the waterflow lines in the afterbody. This can imitate the lines of longer vessels quite successfully; provided the turbulent flow starts forward of the transom. What this amounts to is 'fooling' the water into thinking you've got a longer (faster) hull than you do. Of course this principle can be overdone or overworked but at least in the Coin Collection it seems to work beautifully. This does not mean you should always design heavy vessels with immersed transoms. But, if you can ease the lines aft by immersing the transom, without raising costs, you may gain speed by increasing apparent waterline length.

Shilling is a modern ocean going vessel with her design elements carefully analyzed for utility and applicability to liveaboard voyaging in a rugged extremely seaworthy vessel.

Characteristics

The lines have a heavy wine glass section with long keel, relatively great weight and smooth flow. She was developed by my usual methods. First, choosing a midships section with the best characteristics for the general type and of appropriate area to give the desired displacement and prismatic coefficient. Then, drawing in the section at the forward end of the waterline from sheer half breadth to waterline half breadth. Third, the section at the aft end of the waterline is roughed in. Then a few diagonals are sprung in using a fairly stiff batten. As far as possible, these are “straightened" by changing the sweep of them as necessary. This is most often done by changing the section at the aft end of the waterline. Less often it may involve the alteration of the forward section. When these look good, the diagonals are used to develop some intermediate sections. If these are odd or unfair the diagonals are reworked until acceptable shapes appear. We then work back and forth between sections and diagonals producing the fairest set of lines we can. This produces waterlines and buttocks conforming closely to the ideal lines described by tank test data. These days, since we can do this in the computer to an extraordinary degree of precision, our boats seem to be getting easier and easier to loft and build.

Shilling has a length over all of 22’ 0”, a length on the waterline of 16’6”, a beam over all of 8’0”, and a draft of 4’0”. Her displacement fully loaded is a little over 7,000 lbs.

Rig

The choice of rig reflects a number of considerations important to voyagers. First and foremost the Chinese rig reduces deck work to a minimum. Setting, reefing, unreeling and furling are done from the steering station, even with the bubble hatch closed.

Centralizing control functions reduces physical stress. Sailing is fatiguing enough for most people even with easily handled vessels. Some sailors are not young or physically robust and will be happy to get all the help they can from an easily handled rig.

Another big factor is that an easily handled rig maximizes your speed potential; making it easier to keep the greatest possible sail area up at any given time without being over canvassed. The simple "lift a panel drop a panel" reefing allows keeping the right amount of sail up for any wind condition.

Of special concern to those sailing to out of the way places is the rig's simplicity and ease of repair. The only metal is a few fastenings, some thimbles, and whatever metal parts the blocks have. This makes the rig easy and inexpensive to build or repair.

Further the distribution of area is quite ideal as is control of twist and, with experimentation, camber. This gives the Chinese rig, as worked up here, very good windward performance.

Interior

The interior shown is only one possibility. A flush deck vessel allows plenty of options. A variety of one or two cabin arrangements are possible. The double berth can be eliminated forward, if desired, and the area devoted to a head to starboard and stowage to a port. In that case the foot of one berth would go in under the chart table.

The plans show a divided chain locker so two anchors may be on deck, ready to go at all times, with their rodes self-stowing below. It is helpful when going to sea to roll wet suit neoprene rubber around the rode and tie it so it may be stuffed into the deck pipe to avoid the odd wave top seeping below.

The double berth forward gives 6’4” of sleeping length and plenty of width. The minus is the intrusion of the mast. A filler piece is used to permit enough floor space in the forward cabin to allow placing a bucket head there.

The feet of the main-cabin settee berths telescope under the head of the forward berth. This allows an out of the way place to stow bedding and permits the galley and chart table aft to be larger.

The galley and navigation area extends aft right to the stern. This is quite a large area with a lot of storage for a boat this size. Its one compromise is the folding seat over the center section of the counter to allow you to sit with your head in the dome. In bad weather the boat can be operated quite nicely from inside the closed hatch. In good weather you can stand in the open dome. You can also sit on deck behind the hatchway with your back against the on deck storage boxes or lounge on the deck anywhere going aft only to adjust the self steering gear or adjust a line.

You cannot reduce the deck camber of this design without losing standing headroom. In a similar but larger vessel of this series, the builder apparently could not understand why I had not specified a near flat deck ... and built one. Unfortunately the owner of the boat was left with headroom more appropriate for chimpanzees than human beings.

The interior joinerwork can be done in “fine yacht” style or a workboat style that produces a rugged, attractive interior at low cost; and does so with much less labor than is usual in yacht construction. The basic material in the latter case is nominal 1"x6" boards of anything from pine on up depending on taste and fatness of wallet. If bought planed on all four sides, this gives actual measurements of 3/4"x5-3/4". The edges of these boards are rabbeted; using a router set to cut a 3/8"x3/8" rabbet. The face-of-the-board corners are rounded off with a 1/4" or smaller bullnose router bit. When boards like this are epoxied together edge to edge they form a shiplap seam. Bulkheads are built up piece by piece directly; rather than by measurements and spiling plywood. This is a great time saver. A special drawing in the set shows how this construction appears and how to go about it. This method allows constructing the entire interior of the vessel within three weeks.

Varnish makes a good finish. So does paint; which is a lot quicker. On the harder woods the Deks Olje system is probably the most effective.

Construction

Shilling has strip planking sheathed inside and out with, WEST System™ glass cloth and epoxy resin, the glass cloth being laid transversely. For any degree of strength and stiffness this method is the lightest known to me. It results in a hull lighter than framed carvel, cold-molded, fiberglass, foam cored fiberglass or aluminum construction. Further it is simple and requires little skill and relatively inexpensive materials. All of this means less expensive construction, ease of repair and more carrying capacity for a given displacement.

In my opinion this method is the fastest, most fool proof and durable construction suitable for the novice.

In all but flat bottom boats I recommend lofting everything. There is nothing like trying to draw something full size from careful measurements to help avoid mistakes and aid in understanding what to do and in what sequence.

The molds for this type of construction in this size vessel should be set up upside down as it is much easier to sheathe the outside of the hull and to plank while working down hand. Once the molds are set up, it is relatively simple to place the backbone pieces on top of them and plank over the whole affair. With this type of construction the stem is not rabbeted nor is the sternpost. This makes planking easier. The strips are simply laid against the molds, rough cut to length and then glued and fastened in place with the ends of the strips running out beyond the ends of the hull. When the planking is completed, the plank ends are cut off flush with the outside of the stem, sternpost and transom.

The simplest method of fairing the hull is to cut off any excess epoxy which was not scraped off before it cured with compass planes working down to the wood and then sanding the wood with an ordinary finishing sander. Do not try to use a rotating disk or a belt sander. Anything with a running edge will tend to reduce fairness not promote it. When a fair surface is achieved, the stem and leading edge of the keel are rounded off, and the glass sheathing is epoxied on transversely with the joints butted and the butts staggered between layers.

The sheathing is faired by filling the weave pattern with a mixture of epoxy and MicroLight™ and sanding using boards of masonite with belt sander belts cut to lie flat and fastened to the bottom and handles attached to the back. As a sanding aid, the hull may be lightly painted periodically to show the uneven spots. However the light color of the MicroLight™ and a low angle light should reveal most unfairness at least in the early stages. Once the hull is fair some builders may want to scribe the waterline as it is easier to do upside down.

The simplest and least traumatic way to turn the hull over goes about as follows: If the shop isn't big enough to turn the hull, move it outside. If it is big enough move the hull to one side of the shop and build a triangular frame around it. You can then gradually jack up one side of the hull, blocking it as you go. Increase the blocking on one side and decrease it on the other until the hull has been eased over onto the keel and bilge and can be jacked into upright position. However, in a boat this size the bare hull alone is light enough so you can pad the floor with mattresses and simply get together a few friends to help heave her over by hand. Just make sure you rig some restraining lines.

The deck is probably best built over camber molds right on the hull so you can see what you're doing. Once built you can sheathe the outside. Unfortunately you then have to lift the deck off and turn it over in order to remove the molds and sheathe the under side.

Another method is to set up the building jig upside down' with female station molds and ribbands wrapped around to mark the sheer half breadths. The strips are planked up and the underside faired and sheathed. Then the entire deck, jig and all is lifted up and turned over onto the hull. The deck is glued and fastened to the clamp. The jig is then removed, the deck faired and then sheathed.

This may be a good place to mention “print through”. In recent years we have seen a number of articles explaining that though the hull was apparently perfectly faired and painted by the time the boat was ready to launch you could (horrors) see the planking run and sometimes the grain of the wood in the painted surface. This is because the planking stock goes on slightly changing shape and the resin continues to cure very slightly for some time after the hull is built. This seems like a big crisis and often thousands of dollars is needlessly spent removing the paint again and “refairing” and repainting. In actual fact these changes in the surface are normally only a few thousandths of an inch. A coat of paint is thicker than these “imperfections”. It is just that the human eye is terribly good at seeing these tiny variations in surface fairness, especially in low angle light. Experienced boat builders have always observed this in new boats. What is the solution? Just use a low gloss paint the first year. The second year just the normal sanding and painting will smooth out these visual imperfections at no extra cost over routine maintenance. By the third year at the latest you will have a flawlessly fair surface that can be painted with high gloss paints if you wish. However, I must say we have always found semi-gloss paints to give the best feeling of quality and solidity.

The mast and yard are constructed as one would any other solid round spar. The Chinese sail takes its shape from the battens and running rigging and is cut and sewn absolutely flat. Anyone familiar with canvas work and sail detailing can do the job. If anyone decides they want hollow spars, or carbon fiber spars, we can design those too.

In this vessel we have tried to emphasize simplicity of construction and handling. Further, we have tried to make her as resistant to the stresses of sailing and long term use as possible within the general strength requirements of ocean going yachts. We have taken advantage of modern materials and techniques where they are well proven, readily available and can decrease costs without cutting either strength or durability. On the other hand we have avoided the use of expensive, exotic materials.

Our designs are often characterized by others as having a traditional air. As in most of them, Shilling's form is based largely on function. The only concessions to beauty or tradition lie in those areas where a well-sprung curve or contrasting paint can produce pleasant feelings in the beholder.

Shilling is a small vessel easily handled, fun to sail, inexpensive to build, and allowing a wonderfully free mobile lifestyle.

As you can see we favor small simple vessels of inexpensive, non-exotic, modern construction as a good approach to living aboard.

On long voyages Shilling has an advantage in that, due to great weight, stability, and course keeping ability she may be driven at maximum speed in heavy weather. She is not as tiring as vessels that require more athletic handling. She has a slow easy motion which most people will find comfortable at sea.

In storms she may run before it or heave to under control of her self-steering gear. Being relieved of the necessity of being out on deck, the watch will suffer less fatigue.

I suspect Shilling has a wide enough appeal to do well as a series built boat. She would sell well in modest numbers for a great length of time. She is very capable and roomy; with easily modified interior accommodations due to lack of cabin trunk limitations. The simplicity of the design and construction keep the price low compared to vessels designed by rating rules. This is one reason that we hope to develop an extremely high quality kit version. We’ve got a start on the development work on this but there’s a long way to go.

A large number of Shilling plans have been sold and, along with her larger and smaller sisters from my design board, they form an intriguing fleet.

This vessel offers a simple low stress life for the single hander or live aboard couple. A boat so totally committed to seaworthiness and ease of handling allows one to quite literally "expand your horizons' until the whole world becomes accessible to you at low cost.

| Study Plans | $66 | |

| Complete Building Plans | $899 | |

Farthing 15 / Penny 25 / Stock Plans Order Form / Stock Plans List